Over the course of fifty years, Archer Huntington dedicated his life and considerable family resources to forming one of the world’s great collections of Hispanic art and literature. By the time of his death in 1955, the Society under his guidance had published more than two hundred monographs by its curators, and other internationally noted scholars, covering all major areas of Hispanic culture. Through his financial sponsorship, countless Hispanists were able to conduct their research and publish the fruits of their scholarly labors. In recognition of his scholarship and his invaluable contributions to the advancement of Hispanic studies, Huntington received honorary degrees from Yale, Harvard, Columbia, and the University of Madrid; membership in all of the major Spanish royal academies as well as the national academies of Latin America; appointment to the governing boards of numerous museums, including Spain’s Casa del Greco and the Casa de Cervantes—both of which he was instrumental in founding—the Museo Romántico, the Instituto de Valencia de Don Juan, the Museo Sorolla, and the Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno; and the award of every conceivable Spanish and Latin American medal of honor or distinction, the most notable being Spain’s Orders of Charles the Third, Alfonso the Twelfth, Isabel the Catholic, Plus Ultra, and Alfonso the Tenth.

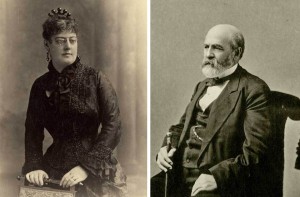

As the only son of one of the wealthiest men in America, Collis Potter Huntington (1821–1900), builder of the Central Pacific Railroad and the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company, Archer Huntington learned at a relatively early age to zealously conceal from the public eye details of his private life and finances. Consequently, the personal accounts of his early fascination with the Hispanic world and subsequent studies, the beginnings and formation of his collections, and the evolution of his concept of a “Spanish Museum,” are to be found only in his private diaries and correspondence. The voluminous correspondence that he maintained with his closest friend and confidant, his mother, Arabella Duval Huntington (1850–1924), which began in earnest with his first trip to Spain in 1892 and continued until her death, has survived in part and provides a wealth of insights into his changing vision of his role and that of his museum in the advancement of Hispanic studies.

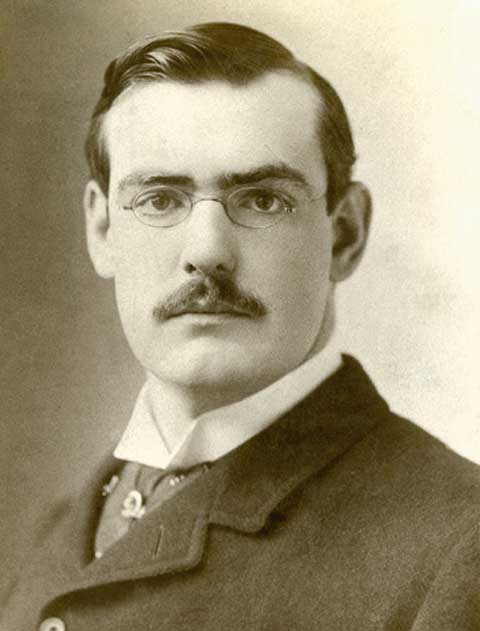

Archer Huntington was born Archer Milton Worsham in New York City on March 10, 1870, weighing an impressive 11 pounds at birth. He took the surname Huntington in 1884 when his mother Arabella Duval Yarrington Worsham married Collis Potter Huntington. Following her marriage to the railroad and shipbuilding magnate, Arabella Huntington went on to form one of the most important art collections of the early twentieth century, focusing on Dutch Old Master paintings, eighteenth-century English portraits, and eighteenth-century French decorative arts. Her collection included such renowned paintings as Rembrandt’s Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, Vermeer’s Woman with a Lute, Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy, and Reynolds’s Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse. On her death in 1924, most of the Collis and Arabella Huntington collections were donated to various museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the California Palace of the Legion of Honor (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco), and The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

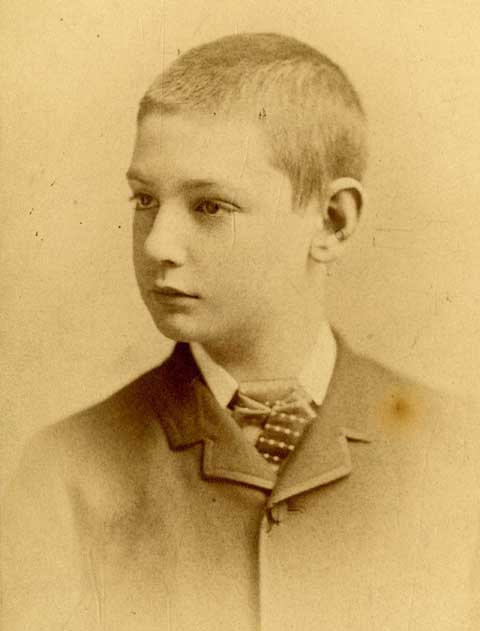

A child of privilege, Archer Huntington attended the best private schools in New York, the Wilson and Kellogg School and the Columbia Grammar School, received the benefit of personal tutors, and enjoyed the experiences and education afforded by foreign travel. In school he was taught Greek and Latin, English history and literature. At home he took up readings in French history with his mother who had become well versed in French arts and letters. His first exposure to the Spanish language in the late 1870s came from the Mexican hired hands on the ranch of his aunt, Emma J. Yarrington Warnken, near San Marcos, Texas; but it was the purchase in London of George Borrow’s The Zincali; or, An Account of the Gypsies in Spain (London, 1841), on his first trip to Europe in 1882 that ignited his lifelong passion for Spain and Hispanic culture. Visits on this trip to the National Gallery in London and to the Louvre in Paris proved to be life-changing experiences that instilled in him a profound love for art and museums. Following his visit to the National Gallery on July 12 the twelve-year-old Archer wrote in his diary: “Read the catalogue until I could not see any more and went to bed. I think a museum is the grandest thing in the world. I should like to live in one.” Two years later in New York his first “museum” took shape, with the art clipped from newspapers and magazines that he displayed in seven small wooden boxes made into “galleries.”

Read the catalogue until I could not see any more and went to bed. I think a museum is the grandest thing in the world. I should like to live in one.

Inspired by Borrow’s Zincali and other books by this author, Huntington began his formal instruction in Spanish at home at the age of fourteen, at first two days a week, then six, with a female tutor from Valladolid whom he enticed into telling him of her native city and Spain. By the age of 16 he had grown to be a large imposing youth of 6’5” who towered above his peers. In 1887 he made his second trip to Europe (London and Paris) again in the summer, although this time he was accompanied by both his mother and father, whose social and business obligations left the teenager free to further explore the great museums and continue his firsthand education in art history. By this trip he clearly had come to discover the usefulness of photographs for furthering his studies, and he noted in his London diary that his collection now filled four trunks.

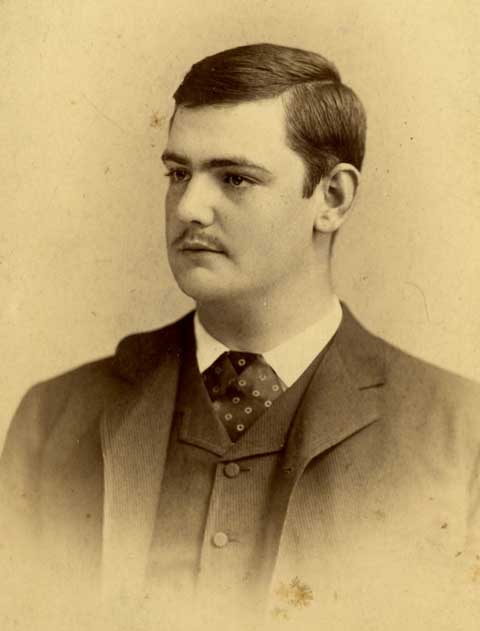

In March 1889, he traveled with his parents on a business trip to Mexico, where for the first time he directly experienced Hispanic culture, attended a formal dinner given by President Porfirio Díaz in Chapultepec Castle, and finally made the decision to establish a “Spanish Museum,” a resolution that would have a profound effect on the rest of his life. In December 1889, his father offered to turn over the management of the Newport News Shipyards to Archer, which forced him to make a final decision and publicly reveal his career intentions. In January 1890, Huntington put his dream into action, as he said farewell to the office of the Shipyards.

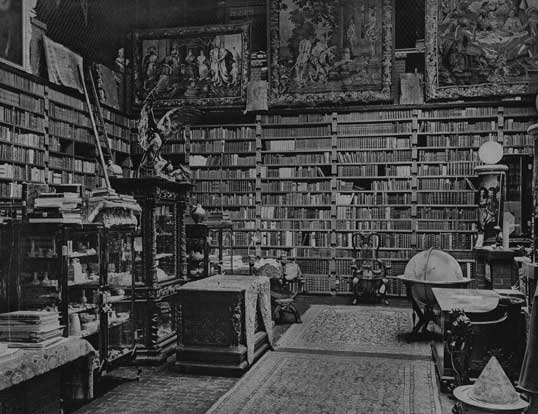

Now officially committed to Hispanic studies and his museum, Huntington started cataloging his Spanish library, which in February 1890 already numbered almost 2,000 books. By the end of that year, he had begun planning his museum. On November 8, 1890, he wrote to his mother, “I am working on more plans for a museum which will amuse you. I would like to know how much wall space is wasted in U.S.A. museums by windows. The windows of an art museum should be pictures.” Once his intentions were known Huntington was forced to suffer the ridicule of friends and family. When he saw his older cousin Henry E. Huntington in December 1890 Henry was rather contemptuous of Archer’s book collecting. Upon Archer’s suggestion that he too should begin collecting books, Henry said that he thought that he could do better with his time. A more poignant encounter took place on January 1, 1891, on the occasion of a visit with his father to the American Museum of Natural History. The banker and philanthropist Morris Ketchum Jesup, the museum’s illustrious president, criticized him for his desire to study a civilization that he considered “dead and gone.” The young Huntington defended himself skillfully against the severe criticism of the distinguished philanthropist, and upon leaving, he received his father’s approval with the words, “Archer I can see that you know what you want, and I believe you can do it. Go on as you like and do the thing well.”

In anticipation of his first trip to Spain, Huntington spent most of 1891 immersed in intensive study of Arabic with a tutor. Though seemingly unrelated to the necessities of travel in Spain, Arabic also formed part of Huntington’s larger scheme of Hispanic studies. Not all of 1891 was dedicated to Arabic and planning for his long-awaited trip to Spain. In February, he made a brief visit to Cuba, from which he gained “many new Spanish impressions,” along with a trunk full of books.

In 1892, the time at last had come for his trip to Spain. Huntington busied himself with surgical studies in the eventuality of serious injury in some remote region of Spain, began work on his translation of the Poem of the Cid, and furiously compiled notes for the journey. Finally, in June he set off for Spain in the company of his paid scholarly companion, Professor William I. Knapp of Yale University. The adventures, experiences, and impressions of this first trip to Spain were recorded by Huntington in minute detail in a copious succession of letters to his mother. Five years later, these very letters, though judiciously expurgated, became A Note-Book in Northern Spain (New York, 1898).

Huntington married his cousin Helen Gates Criss in London in the summer of 1895. That same year, in collaboration with the De Vinne Press in New York City, he began to publish a series of facsimiles of rare books and manuscripts taken primarily from his own library, in the hope that these valuable texts might be preserved and made available to scholars. The following spring saw his return to Spain, and his library grew by leaps and bounds. In February 1897, his father made the couple a gift of an estate named “Pleasance” in Baychester, located in the eastern Bronx on Long Island Sound, on the heels of which followed the gift of three Spanish paintings from Collis’s collection, which included Antonis Mor’s portrait of the Duke of Alba (1549). Finally, Huntington had space for a proper library, and its planning and construction filled the remainder of the year. This endeavor provided valuable practical experience for the eventual design and construction of his “Spanish Museum.”

Antonis Mor

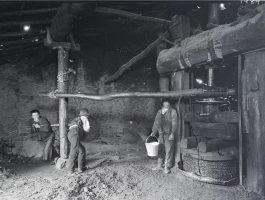

His library completed and installed at “Pleasance,” and having seen the publication of the first volume of his edition of the Poem of the Cid (New York, 1897), Huntington set off for southern Spain in 1898, this time his focus is books and archaeology. The rare books that he so eagerly sought he found in Seville in the library of the Marquis of Jerez de los Caballeros, but he would have to wait another four years before he could negotiate their purchase. On discovering that the French archaeologist Arthur Engel had abandoned his excavations at Itálica, Huntington arranged to lease the site and began his own excavations in January 1898. The treasures unearthed at Itálica, an endeavor cut short by the outbreak of the Spanish American War, along with the objects acquired from the excavations of George Bonsor at Carmona, soon formed the nucleus of his archaeological collections.

Huntington kept defining his concept of the “Spanish Museum” in 1898, as he told his mother, “My collecting has always had for it a background—you know—a museum. The museum which must touch widely on arts, crafts, letters. It must condense the soul of Spain into meanings, through works of the hand and spirit. . . . I wish to know Spain as Spain and so express her—in a museum. It is about all I can do. If I can make a poem of a museum it will be easy to read.” As he had hoped, Huntington’s travels through Spain in 1892, 1896, and 1898 gave him new insight into the Spain that had escaped him in books. By 1898, he had come to the realization that his years of study on Hispanic culture had produced only a sterile, academic, and incomplete portrait of Spain. Through personal interaction with individuals from all levels of society, and in particular those of the countryside, Huntington felt that finally he had discovered the soul of Spain in its people.

MARQUIS OF JEREZ DE LOS CABALLEROS, 1914

Joaquín Sorolla

Huntington spent the next six years in a flurry of activities, including the publication of some forty facsimiles, although his primary focus remained the creation of his museum. Following the death of his father in 1900, Archer inherited the resources to make major acquisitions and to begin a serious collection of art. In January 1902, he purchased the much-coveted library of the Marquis of Jerez de los Caballeros, (Sorolla portrait A1942) the finest private collection of early Spanish literature of the era. While aware that the acquisition of this invaluable library would inevitably be the subject of controversy in Spain, Huntington remained confident in his belief that this would ultimately lead to the advancement of Hispanic studies. On the eve of the founding of the “Spanish Museum,” Huntington again traveled to Europe in search of more objects to fill out his already-impressive collections.

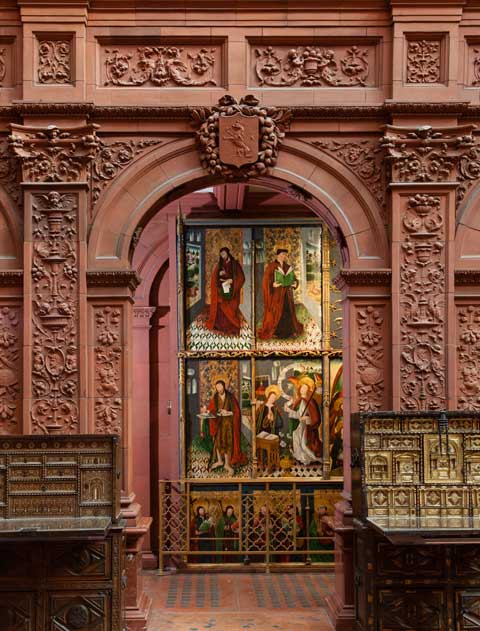

Finally with land purchased in upper Manhattan and an initial endowment set aside, on May 18, 1904, Archer Huntington executed the Foundation Deed for a public Spanish library and museum, to be called The Hispanic Society of America. The object of the institution was the “advancement of the study of the Spanish and Portuguese languages, literature, and history.” In little more than a year the building was in place, but two more years were spent in the careful arrangement of the collections, all directly supervised by Huntington himself. In anticipation of the inauguration of his museum, he continued adding to the collections with the important acquisition in Paris of a monstrance made in 1585 by Cristóbal Becerril, as well as the famous portrait of the Duchess of Alba (1797) by Francisco de Goya. With the formal inauguration of the Hispanic Society on January 20, 1908, Huntington at last had in place the vehicle through which he could pursue his fixed purpose of being the champion of Spain in America.

The doors of the Society had been open to the public for only a few months when Huntington again set off for Europe, where he discovered the paintings of Joaquín Sorolla on exhibition in London at the Grafton Gallery. Given the profound influence that this encounter ultimately would have upon the lives of Sorolla and Huntington, as well as the Hispanic Society, it is unfortunate that he failed to record in his diary his own impressions. He unquestionably was captivated by Sorolla’s work, for he immediately initiated plans through agents in London for an exhibition at the Hispanic Society the following year. The exhibition was an immediate sensation attracting nearly 160,000 visitors from February 4 through March 8, 1909. Huntington’s first special exhibition was an unparalleled success, conferring international recognition and acclaim on both Sorolla and the Hispanic Society. From this exhibition Huntington had the opportunity to acquire some of Sorolla’s best works, including After the Bath (1908), Beaching the Boat (1903), and Sea Idyl (1908). The success of this exhibition encouraged Huntington and Sorolla to arrange for another exhibition two years later at the Art Institute of Chicago and at the City Art Museum of St. Louis. Over the next twenty years, Huntington and the Hispanic Society sponsored a number of significant temporary loan exhibitions, yet none approximated the popular appeal or the impact of the Sorolla exhibition.

Energized by the recent triumph, Huntington renewed his search for books and art objects for the Hispanic Society, adhering to his grand scheme of building library and museum collections touching on all facets of Hispanic culture. Even though Sorolla and others couraged him to buy in Spain, Huntington maintained his long-established policy of only acquiring significant early works of art outside the Peninsula, such as Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of a Little Girl, which he purchased in 1908 from Duveen Brothers in London, with his mother’s encouragement and financial assistance. Another major addition to the collection came from Arabella when she purchased Velázquez’s portrait of Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares (ca. 1625-26) from Duveen for the unprecedented price of $650,000, which she immediately presented to the Hispanic Society in memory of Collis P. Huntington.

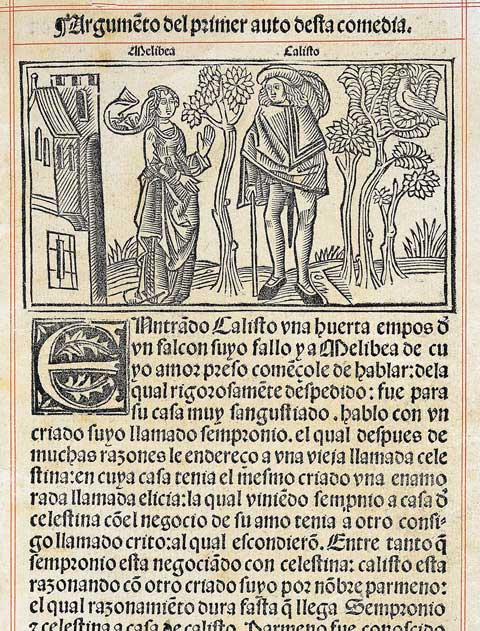

The bulk of the Society’s museum collections were purchased personally by Huntington from major art dealers and on occasion at auction, in Paris, London, and New York. In fact, the same policy applied in general to library acquisitions, as he acquired very few rare books and manuscripts in Spain following the purchase of the Jerez library. The famous first edition of La Celestina ([Burgos, 1499?]) that Huntington had been unable to buy in 1895 from Quaritch in London finally arrived at the Hispanic Society as a gift from J. Pierpont Morgan. He preferred to purchase whole catalogued collections prepared expressly for the Society by the antiquarian book dealer Karl W. Hiersemann of Leipzig. For ten years, from the founding of the Society until the outbreak of World War I, he dealt almost exclusively with Hiersemann, adding books and manuscripts by the tens of thousands to the library.

Fernando de Rojas

Huntington continued to add to the Society’s now extensive museum collections, buying works by both early and contemporary artists. While in Madrid in 1912, he visited the king and queen, who inquired into his acquisitions of Spanish art. His response, by then customary, assured the monarchs that he had no intention of depriving Spain of its artistic heritage. Huntington fully appreciated the concerns of the Spanish monarchs, for he was ashamedly aware of the insatiable appetite for European art and culture of his fellow Americans.

Juan Vespucci

The outbreak of World War I in Europe effectively brought to an end Huntington’s active pursuit of acquisitions for the Hispanic Society. Representative of the significant acquisitions from this final period are the world map of 1526 by Juan Vespucci and the 10th-century ivory box made by Khalaf at Madinat al-Zahra’, near Córdoba. By war’s end, Huntington had for the most part lost interest in substantially expanding the art, rare book, and manuscript collections of the Society, perhaps in part due to the realization that years of work still lay ahead in researching and cataloging the material already amassed. He also had begun to sense the passing of an era, one in which many of the greatest art collections in the United States had been built. For Huntington and the Hispanic Society, one major acquisition however did await completion: Sorolla’s commission on the provinces of Spain, which was completed in 1919, but not installed and opened to the public until 1926.

Anna Hyatt Huntington

Huntington also saw a chapter of his own life coming to a close, that of scholar and collector, as he began to form a professional staff to conserve and research his collections. Writing at the end of 1920, he observed that “the staff is gradually taking shape, and someday I hope that we may issue through them a fine set of monographs. I hope to get each one interested in a single subject, so that they may become expert in each case along a definite line.” He recently had hired a group of young women in their twenties to work in the Library Department, all freshly graduated with degrees in library science from colleges such as Simmons in Boston or Gallaudet in Washington, D.C. After only a few months as librarians, Huntington assembled them one day and told them of his plans to form a Museum Department composed of specialist curators for each major area within the collections. He proceeded to offer them the opportunity to select a new field of specialization, which they eagerly accepted: Elizabeth du Gué Trapier, Paintings and Drawings; Beatrice Gilman Proske, Sculpture; Alice Wilson Frothingham, Ceramics; Florence Lewis May, Textiles; and Eleanor Sherman Font, Prints (photos). Along with Clara Louisa Penney, bibliographer in Manuscripts and Rare Books, they began to research and catalogue the Hispanic Society’s collections, a seemingly endless task that would take them some 50 years to complete. As Huntington had hoped, in time they became true experts, first issuing catalogues of the collections, followed by scholarly monographs. Many of these remain fundamental references in their field, such as Proske’s Castilian Sculpture (1951), May’s Silk Textiles of Spain, Eighth to Fifteenth Century (1957), and Frothingham’s Spanish Glass (1963).

Marion Boyd Allen

Following his second marriage in 1923 to the noted sculptor Anna Vaughn Hyatt, Huntington began to plan for the addition of appropriate permanent sculpture on the terrace in front of the Society. The addition of yet another building for galleries and storage on the north side of the terrace on 156th Street provided the proper setting for Mrs. Huntington’s sculpture. In 1927 her monumental equestrian bronze of El Cid was placed in the lower terrace, immediately becoming the unofficial symbol of the Hispanic Society. In the years that followed, the collections of the Society continued to grow through purchases and gifts, many from its founder, although Huntington himself no longer made any major acquisitions. As would be expected, in his final years he became less involved in the daily operations of the Society, yet he retained total administrative authority until his death in 1955. Besides financial bequests, Huntington’s final gift was a treasure trove of drawings, manuscripts, and rare books that he had reserved for himself over the years in a personal vault within the Hispanic Society.

Archer Huntington’s greatest legacy to Hispanic studies remains the Hispanic Society itself, with its invaluable museum and library collections. Today, his “Spanish Museum” not only serves as an essential resource for the study of Hispanic culture in all of its varied manifestations but, through its vast collections, offers unlimited research opportunities for future generations of scholars. In this sense, as Huntington had speculated in the 1920 letter to his mother, his greatest contribution to Hispanism indeed was “preparing the way for others.”

Archer Huntington’s philanthropy and “ventures into museum building” were not limited to the Hispanic Society. After founding the Hispanic Society in 1904, Huntington invited other institutions with which he was associated to relocate to Audubon Terrace. These included the American Numismatic Society (1907), The American Geographical Society (1910), the Church of Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza (1912), The Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation (1916), and the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1923). Ultimately, Huntington not only donated the land to all of these institutions, but also paid for the construction of their buildings, with the exception of the Church of Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza. In Spain, he was instrumental in the founding of the Museum of the House of Cervantes in Valladolid and the Museum of the House of El Greco in Toledo. In the years that followed he founded Brookgreen Gardens (1930) at Murrells Inlet, South Carolina, and The Mariner’s Museum (1932) at Newport News, Virginia.

In his later years, Huntington was equally generous with donations of family possessions and properties. Collections of art and antiques were presented to the California Palace of the Legion of Honor of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (1927), the Yale University Art Gallery, in memory of Arabella (1927), The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1927), and The Charleston Museum in 1931-32. Large tracts of land were donated for museums, parks, and nature preserves, including the 15,000 acres that comprised his Adirondack Great Camp Arbutus for the Archer and Anna Huntington Wildlife Forest Station, Newcomb, New York, to the State University of New York College of Environmental Forestry in Syracuse (1932); his private residence in New York City, 1089 5th Avenue, to the National Academy Museum and School (1940); 500 acres to the Palisades Interstate Park Commission, Haverstraw, New York (1943); his father’s 200-acre Camp Pine Knot on Raquette Lake, the first Great Camp in the Adirondacks, to the State University of New York Cortland as a memorial to Collis Potter Huntington; and he willed 1,017 acres in Redding to the State of Connecticut for the Collis P. Huntington State Park, which opened to the public in 1973 following the death of Anna Hyatt Huntington. Generous to a fault, Archer Huntington never sought personal recognition or memorials, which is why during his lifetime he did not allow any institution that he founded to bear his name. Huntington’s institutions stand today as lasting memorials to the accomplishments and generosity of one of America’s greatest philanthropists.

The Hispanic Society has retained a major focus on scholarly research in keeping with its mission, but since the 1990s a renewed emphasis has been given to making the collections accessible to new and broader audiences. To this end, temporary exhibitions taken from the collections, and accompanied by catalogues, were mounted at the Hispanic Society in the 1990s. Even more significant are the major exhibitions organized in recent years at museums in Spain Mexico, and the United States that have reached new audiences numbering in the millions Past Exhibitions at the Hispanic Society.

The collections, and particularly the Society’s permanent exhibitions, continue to be energized through major acquisitions in all areas, by both gift and purchase, with works such as Nonell’s La Roser (1909) Murillo’s The Prodigal Son (circa 1656–1665); Rodríguez Juárez’s De Mestizo y de India (circa 1720); Saint Michael Archangel (Ecuador, 1700–1750); Sunyer’s At the Moulin Rouge (1899); a Peribán lacquer batea (Mexico, 1600–1700); and a Barniz de Pasto writing desk (Colombia, circa 1684). Support for the Society’s programs and collections has been provided since 1998 by the Friends of The Hispanic Society of America, as well as from its counterpart in Spain, the Asociación de Amigos, which has promoted the Society and all of its activities from its headquarters in Madrid. Not content with the remarkable accomplishments of the past hundred years, the Hispanic Society now looks forward with ambitious plans to expand acquisitions, programs, exhibitions, and facilities that will ensure continued vitality and success through its second century.

Additional Suggested Readings

Bennett, Shelley. The Art of Wealth: The Huntingtons in the Gilded Age. San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 2013.

Codding, Mitchell A. “Archer Milton Huntington, the Champion of Spain in America.” In Spain and the United States: The Origins of American Hispanism, ed. Richard Kagan. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002, 142–170.

———. “A Legacy of Spanish Art for America: Archer M. Huntington and The Hispanic Society of America.” In Manet/Velázquez: The French Taste for Spanish Painting. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003.

———. “Sorolla and The Hispanic Society of America.” Sorolla and America. Eds. Blanca Pons-Sorolla and Mark P. Roglan. Dallas: The Meadows Museum, 2013. 55-67.

The Hispanic Society of America, Museum and Library, 1904–1954. New York: The Hispanic Society of America, 1954.

Lenaghan, Patrick, et al., eds. The Hispanic Society of America: Tesoros. New York: The Hispanic Society of America, 2000.

Huntington, Archer Milton. A Note-Book in Northern Spain. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1898.

———, ed. and trans. Poem of the Cid. 3 vols. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1897–1903.

Proske, Beatrice Gilman. Archer Milton Huntington. New York: The Hispanic Society of America, 1963.